Is it true that the Atlantic Slave Trade impeded long-term economic development and created political disorder in Africa?

By Lucy Morris

Edited by William Harrop

Abstract

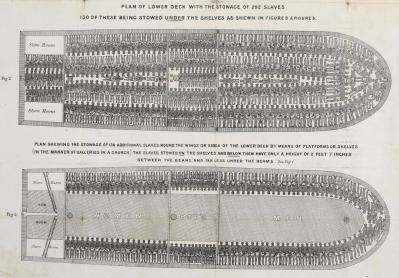

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the sea-faring nations of Europe engaged in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, transporting millions of human beings on squalid, cramped ships from West Africa to European plantations in the Americas. In this superb article, Lucy Morris analyses the destructive influence of this tragedy on Africa, framing the study in terms of its political and economic impacts to reveal just how deep the scars go.

It would be absurd to disregard the impact of the forced migration of roughly 12 million Africans to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries, not least because this number omits deaths by maltreatment or disease before even boarding the ships.[1] Historians such as John Parker and Basil Davison deem the impact not only devastating, but ‘initiated’ by the Atlantic Slave Trade alone.[2] Opposition from Eltis and Jennings proposes that the resilience of Africa has been grossly understated, thus denying any long-term consequences.[3] The former runs the risk of ignoring Africa’s history, agency and capacity for corruption. The latter borders on erasing the issue altogether. The question requires deconstruction. A common methodology is comparative study: contrasting the political systems/economic development before and after the Atlantic Slave Trade. Other historians ask whether slavery already existed in Africa, how much blame can be placed on the venality of African leaders, or the benefits to the African economy – though arguments for a positive political outcome are rare.[4] None of these factors negate that, at the very least, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade served as a ‘catalyst for the expansion and intensification of slavery in African societies’.[5] At its most insidious, it inspired political violence, drained regions of their most able-bodied labourers, and justified prejudiced perceptions of Africa as an inferior power: one to be exploited beyond the abolition of slavery.[6]

It is hardly contested that the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade had detrimental economic and political consequences. Northrup’s influential analysis of estimated annual slave exports finds ‘phenomenal growth’ until the end of the 18th century: here, slave exports annually averaged 17,400, falling to around 9,200 before rising sharply by the 1830s.[7] Crucially, they plummet with British abolition in 1807.[8] Similarly, Fage synthesises research to conclude that a ‘slave economy’ was established in much of Sudan by the 14th century, spreading to surrounding regions by the 15th century.[9] The 1999 Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database figure of more than 27,000 slaving voyages from Africa to the Americas (1527-1867) has been deemed definitive.[10] What is contested is whether the economic development or political order were truly damaged and, if so, was it solely the fault of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade?

Comparative studies enable us to explore this. It stands to reason that the Trade would have hit hardest, had slavery not existed previously. The notion that Africa naturally responded to high foreign demand with slave exports is not grounded in fact. Firstly, slaves were initially kidnapped by Portuguese mariners in the 1440s.[11] Secondly, Norris and Dalzel’s work on Dahomey in the late 18th century indicates that Africa, having an inherent propensity towards slave-trading, was merely an advantageous viewpoint for European slave-traders looking to ‘justify their business’.[12] Slavery did exist in West Africa before the advent of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, but this does not make it an inherent component to the functioning of African politics or economics.[13] Analysis of the Ashanti society defines five types of enslavement, only two of which were comparable with European ideas.[14] First is Odonko: a foreigner bought solely to become a slave, secondly is Domum: a person given as a tribute from a subdued nation.[15] Furthermore, the rights of these slaves exceeded the rights of slaves in the colonies.[16] The rights of Ashanti slaves were similar to that of freemen; in many states, every citizen was a slave to the king. Slavery existed, though, potentially only in societies impacted by major trading routes.[17] More research is needed, certainly on stateless societies.[18] But perhaps the impact came from the influx of external trade as a whole. Before the 15th century, European powers had been preoccupied with maritime fighting, keeping their commercial interests private.[19] But with increased sea-navigation, Europe saw that ‘West Africa could become a valuable region with which to trade’.[20] However, Davison argues that commerce was relatively peaceful: it ‘collapsed into loss and sorrow’ only with the advent of the Slave Trade.[21]

First then, African economic development, prior to the Slave Trade, must be examined. Pre-colonial Africa is often depicted as ‘at the level of a subsistence economy’, a continent held back by natural, ‘material constraints.’[22] Not only is this perception of Africa misguided, it is also a generalisation spanning a continent. Diop takes a different angle, comparing African economies with one another, rather than with Europe. Some tribes, such as the LemLem in Southwest Ghana, had engaged in barter trade since the Carthaginian period and commerce along the borders of Africa exchanged gold that was not money.[23] However, the Tarikh es Sudan indicates there were modern systems across the detribalised kingdoms and merchant classes in Ghana and Songhai.[24] Though the use of salt or copper as currency seems peculiar, it is perfectly reasonable that the rarest substances should be used, rather than the abundant gold.[25] Similarly, in reassessing the textile industry, Thornton concludes that pre-colonial African production, technology and trade was strong.[26] The decision to continue hand production rather than machines was ‘mistaken’, but this can only have been clear in retrospect.[27] Thus, there was nothing inefficient or primitive about African economic decision-making.

Politically, Africa had functioned consistently from the first to the nineteenth century.[28] To define Africa’s pre-colonial politics, Diop uses a combination of testimonies and the constitution of (what is now) Burkino Faso.[29] These accounts detail the systems of heredity that consisted of emperors, a form of Electoral College with four dignitaries, a Prime Minister, and assistants – each governing one region. Diop emphasises that this system was fixed as well as ancient.[30] If we are to equate continuity with stability, then up until the Slave Trade, African politics had been stable. Furthermore, this system listened to the complaints of slaves and labourers alike.[31] The existence of slavery before the Trade is simply not comparable. Slavery within pre-colonial Africa did not rob the continent of 12 million workers, nor rob those workers of their rights and culture.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade impacted economic development and political order because it was new: not only on a much larger scale, but of a much more sinister nature than previous instances of slavery. The Trade was built on prejudice, without empathy for Africa’s economic development or understanding of their political order. For example, French missionary Pere Labat was not the only foreign imperialist wishing to ‘induce [Africa] to offer “all their labour, their trade and their industry”’ by getting them ‘hooked’ on traded goods.[32] Europe indeed siphoned labour from the nation. This is not to say that Africa was passively imposed upon; the notion of ‘Extraversion’ explores the role of African leaders attempting to create relationships with foreign powers.[33]

Indeed, it could be beneficial for African leaders to exploit those beneath them.[34] But Extraversion, amongst many other components to this debate, can be overstated and oversimplified. Most African people and industries could not benefit.[35] Not only because they had no say in the matter, but because the African economy was not stagnant, or in need of stimulation.[36]

Another oversimplification would be to argue that economic development or political order were affected only by Western interference. Africa was not a blank canvas whose history began with Atlantic trade. Much of eastern and southern Africa had withstood the Muslim slave trade, with primarily women being shipped eastwards, or to North Africa.[37] In this sense, the Atlantic Trade affected regions of (primarily West) Africa differently.[38] Internal religious disputes lead to political unrest before the interference of the West: the execution of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, following her claims that Jesus, Mary, and St. Francis were Kongolese, serves as an example of this.[39] But, just because Africa had not been a peaceful utopia of ‘benevolent kings’, it does not mean that further political disorder was not created by the Trade.[40] In this very case study, many Antonians were sold by war lords, to be shipped across the Atlantic.[41] The Atlantic Slave Trade intersected with existing political issues. As ever, some people were freemen, others were slaves within Africa, but now many were exported as punishment – or as needed – to meet demand. Thus, a third class of people emerges who were regarded more as commodities than the freemen and slaves. As Joseph Calder Miller puts it in Way of Death, the change lay in ‘African perceptions of the relationship between goods and people’.[42] Perhaps it was less a creator of disorder and more of a catalyst that put slavery on a new scale, racializing and dehumanising more than slavery within precolonial Africa.[43]

Were the economic and political impediments long-term? Were they the result of the Slave Trade, or Atlantic commerce at large? Eltis and Jennings’ analysis of research by Gerhard Liesegang pits data including slave exports against data without.[44] Between the late 18th and late 19th centuries, Western Africa’s annual average per-capita trade grew by only 0.1%.[45] Including slave exports, Africa was slow to benefit at all.[46] When accounting for Africa’s size, revisions find that the economy recovered.[47] Nonetheless, had the Slave Trade continued, the result would have been ‘severe dislocation and restructuring for Africa’.[48] This is clear through the situation post-abolition. The Atlantic demand for exported goods meant that, even when the slave trade ended, the volume of enslavement within Africa remained high.[49] Thus, older historiography, which credits the Atlantic economy as a stimulant, is fundamentally flawed. Firstly, it does not consider the immense commercial contributions of Africa.[50] Secondly, it denies the long-term impact of unprecedented foreign demand.

The economic and political consequences of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade are still tangible today. It has been referred to as ‘Africa’s Holocaust’.[51] This is reasonable, for while the scale of its economic and political repercussions should not be ignored, neither should the rest of Africa’s history. It is unreasonable to treat the Trade as a stimulant to an untouched land, even if the damage is acknowledged. But defending the resilience of Africa’s economy, only to deny the devastation wrought by the Trade is as misguided as it is immoral.

[1] Parker & Rathbone (2007), 77.

[2] Davison (1998), 132.

Parker & Rathbone (2007), 77.

[3] Eltis & Jennings (2001), 937-959.

[4] Bayart (2000), 217-267.

[5] Parker & Rathbone (2007), 77.

[6] Ibid., 7, 77.

[7] Cookey (1980), 365.

[8] Ibid., 365.

[9] Fage (1969), 404.

[10] Parker & Rathbone, (2007), 79.

[11] Ibid., 77.

[12] Fage (1969), 393.

[13] Ibid., 394.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Cookey (1980), 364-365.

[19] Davison (1998), 131.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 132.

[22] Diop (1986), 126.

[23] Ibid., 126-129.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Thornton (1990-1991), 1-19.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Diop (1986), 41.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., 41-43.

[31] Ibid., 43.

[32] Eltis & Jennings (2001), 936.

[33] Bayart, (2000), 217-218.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Parker & Rathbone (2007), 80-81

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid., 5.

[38] Ibid., 79.

[39] Ibid., 72-76.

[40] Ibid., 27-28.

[41] Ibid., 72.

[42] Miller (1988), 40.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Eltis & Jennings (2001), 956-957.

[45] Eltis & Jennings (2001), 956.

[46] Ibid., 957.

[47] Eltis & Jennings (2001), 956-957.

[48] Ibid., 959.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid., 936.

[51] Parker & Rathbone (2007), 80.

Bibliography

Ajayi, J.F.A. & Oloruntimehin, B.O. (1977), ‘West Africa in the Anti-Slavery Trade Era’, in J. E. Flint (ed.), Cambridge History of Africa. Volume 5, From c.1790-c.1870, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 200-21.

Bayart, J-F. (2000), ‘Africa in the World: A History of Extraversion’, African Affairs 99, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 217-267.

Cookey, S.J.S. (1980), ‘Trade without Rulers: Pre-Colonial Economic Development in South-Eastern Nigeria, David Northup’ (review), The International Journal of African Historical Studies 13, 364-369.

Davison, B. (1998), West Africa Before the Colonial Era: A History to 1850, Harlow: Longman.

Diop, C. A. (1986), Precolonial Black Africa, trans. H.J. Salemson, Westport: L. Hill.

Eltis, D. & Jennings, L. C. (2001), ‘Trade between Western Africa and the Atlantic World in the Pre-Colonial Era’, American Historical Review 93, 937-959.

Fage, J.D. (1969), ‘Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Context of West African History’, The Journal of African History 10, 393-404.

Lovejoy, P.E. (1989), ‘The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on Africa: A Review of the Literature’, The Journal of African History 30, 365-394.

Manning, P. (1983), ‘Contours of Slavery and Social Change in Africa’, The American Historical Review 88, 825-857.

Miller, J.C. (1988), Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1830, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Northrup, D. (1978), Trade without Rulers: Pre-Colonial Economic Development in South-Eastern Nigeria, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parker, J. & Rathbone, R. (2007), African History: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thornton, J. (1998), Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thornton, J. (1990-1991), ‘Precolonial African Industry and the Atlantic Trade, 1500-1800’, African Economic History 19, 1-19.